In Science, Inspiration Can Come From Unlikely Places A mom reached out to a scientist with a novel idea for an experiment. Years later, her hunch has blossomed into a published scientific study.

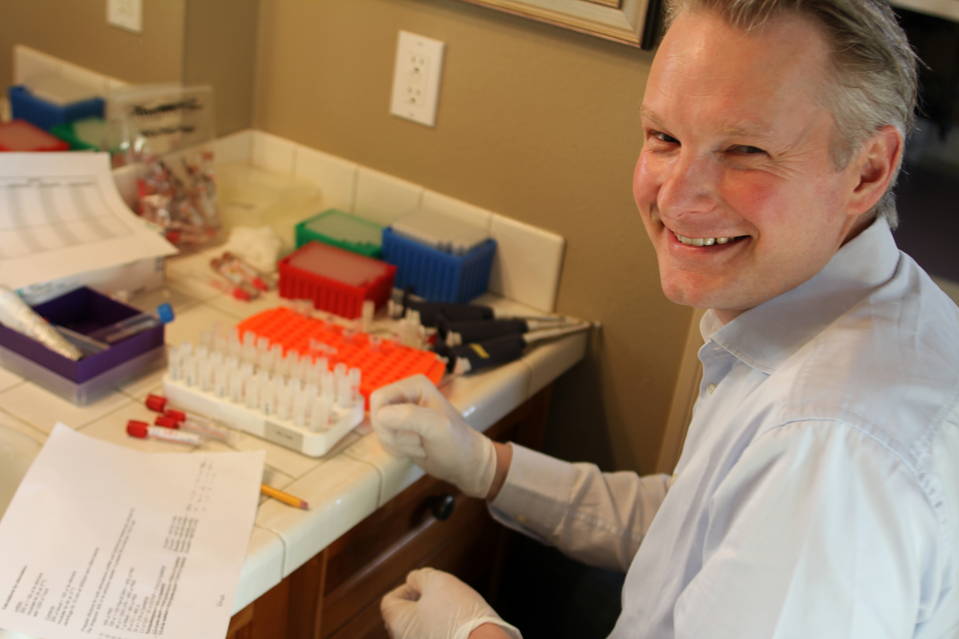

Eicke Latz gathering data for his cyclodextrin studies. Photo: Chris and Hugh Hempel

By

Amy Dockser Marcus

Updated April 6, 2016 2:08 p.m. ET

In science, ideas can come from anywhere. Still, Eicke Latz was surprised to get an email in 2010 from a stranger proposing an experiment.

Dr. Latz and other researchers had just published a study in Nature proposing that cholesterol crystals that form in the arteries may help trigger inflammation and heart disease. The scientists wondered in the paper if finding drugs that might dissolve the crystals could make a difference in treating or even preventing the disease.

One of the readers of Dr. Latz’s paper was Chris Hempel of Reno, Nev., the mother of twin girls with a rare and fatal cholesterol-metabolism disorder called Niemann-Pick Type C disease. Her children were receiving cyclodextrin as part of an experimental treatment approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Ms. Hempel wondered if cyclodextrin might work to dissolve cholesterol crystals. Dr. Latz said the idea was intriguing, and he set out to test it.

Years later, Ms. Hempel’s inkling has turned into the focus of a newly published scientific study in the journal Science Translational Medicine. Dr. Latz lists Ms. Hempel as one of the co-authors.

“In the end,” he says, “the question turned out to not be so simple to answer.”

Here are edited excerpts of the conversation with Dr. Latz about how those most affected by a particular disease can end up helping to generate science.

WSJ: Have you ever pursued a suggestion from someone who isn’t a scientist?

Dr. Latz: Typically not. If the concept is maybe written up in a very clear way or it is a simple concept you may actually get ideas from people who are not scientists. Those are sometimes the best ideas, because when you have an education on a certain subtopic you are always a little bit biased. You understand what other people have written about the topic, you understand all the knowledge around the topic, or at least you think you understand it, but then sometimes the most obvious things don’t really stay in your mind. They don’t come out because you think too complicated.

WSJ: Can you expand on what some of the advantages an educated patient advocate, but not a trained scientist, might have in coming up with an idea for an experiment?

Dr. Latz: One thing is they probably have a lot of passion for what they read up on and for what they come up with, just because it affects the lives of their loved ones and this is a driving force, to really grasp everything around the disease. They want to get [at] something novel and…want to find something new so they can have a new therapy for their kids or people that have a disease. So I think it’s a special driving force that is in those people.

WSJ: What would be some of the limitations of working on ideas that come from people who don’t have any specialized science training?

Dr. Latz: I don’t think there is a limitation because, in the end, it is something you can test, in a mouse or a test tube or an experiment. So if the idea is a good idea, it comes out perfectly well and if it is a bad idea or an idea that is not justified, it will not show the answer.

Addison and Cassidy Hempel, twins with Niemann-Pick Type C disease, take an experimental drug now being tested in heart disease too. Photo: Chris and Hugh Hempel

WSJ: What factors limit more widespread collaboration between scientists and the public?

Dr. Latz: The information we typically get is from peer-reviewed journals. That is something that is not typically open to the general public...it is hidden between certain paywalls because people have to pay for viewing those articles. [But] there are more and more open access policies in science publishing so that other people actually can have access to the scientific literature. That is only one layer. The other layer is the language itself sometimes is a little bit cryptic. It is specialized. You always have to assume the reader has a certain knowledge level about what you write about.

Write to Amy Dockser Marcus at amy.marcus@wsj.com